I awake gasping for breath. Panic rises in my chest as claustrophobia closes in around me. I thrust my nose and eyes out of the dark cocoon that is my sleeping bag and, as I inhale the frigid air, I talk myself down. Again. “Chill out, Taylor. You’re in the Himalaya.” Periodic breathing, also known as altitude apnea, is when you simply stop breathing in your sleep and your body, recognizing the lack of oxygen, tries to catch up all at once. It is one of the many discomforts of the high alpine and it’s getting worse as we go higher and higher. We have been living at high altitude for more than a week. Good sleep remains elusive.

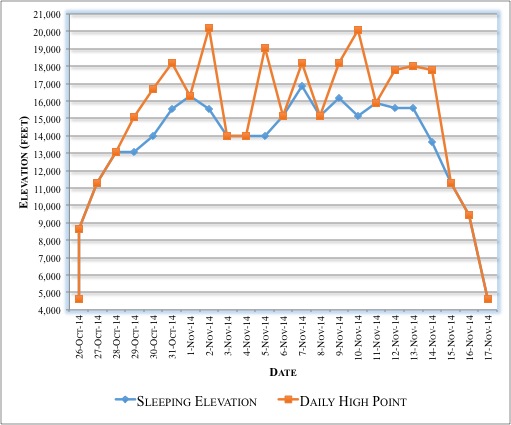

Elevation Profile for our time in the Khumbu region, including the elevation at which we slept at night and each high point we hit during the day.

I survey my surroundings by touch. I’m wearing the same base layers that I do every night, which are a little stiff and have a distasteful aroma, but are the cleanest clothes I have. My sleeping bag liner is bunched and twisted tightly around me. Inside my sleeping bag, I’m wrapped in my big, marshmellowy down jacket to add another layer of warmth. My day clothes are wadded up near my waist, low enough that I don’t have to smell them. Stowed at my feet are extra batteries, camera, IPhone, 2-way radios, canisters of fuel, and two water bottles (once boiling hot, but now tepid). Another zero-degree sleeping bag is draped over the top of Michael and I. I can see Michael’s long hair, which he refuses to cut, poking wildly out of the small opening of his bag. With the temperatures well below freezing, we have to keep everything warm enough to function and our bodies are the only sources of heat up here.

Michael and I huddled in our crowded yellow home at Island Peak base camp, snug with all of our gear stuffed inside our sleeping bags to make sure it was warm enough to function in the morning.

Michael stirs, a product of being almost telepathically connected and him sensing that I’m awake. His alarm is set for 2am and it hasn’t gone off yet. “Wanna go?” he asks. I grunt, leaving it open to interpretation. He turns on his headlamp and begins the contortionist act of getting dressed in a tiny space while trying to avoid contact with cold things (everything is cold). I look up at the beautiful, sparkling ice on the ceiling of our tent and then swallow my irritation as he bumps the side and ice crystals rain down on my face. It will be my turn next.

Our excitement to climb today is diminished by the fact that there are many other people doing the same thing (although no one else is doing it self-supported). With more than 100 tents at base camp and between 25 and 50 people attempting the summit every day, the aptly named Island Peak (~20,300 ft) is the most climbed high peak in the Himalaya.

The upper section of Island Peak base camp. There were well over 100 tents strewn about the camp, some of them semi-permanently established for employees of large guiding companies.

After a quick and tasteless breakfast, we start off, the last group to leave base camp. It’s pitch black. I see a train of headlamps moving slowly up the mountain above us. The ants go marching one by one I start singing to myself. Now well-acclimatized, we make great time, passing group after group on the rocky trail, hoping we can make it by as many people as possible before hitting the “bottleneck” sections. “Namaste!” I say with artificial cheeriness as we pass. In two cold hours, we’ve reached the snow and managed to pass all but one team. It’s still dark and inhumanely cold, and now the wind is gusting. We get out our crampons and ice axes, but I make a rookie mistake: my crampons are set for different boots! For the next 20 minutes, I alternate between frantically prying and banging the frozen metal lever to adjust the size and sticking my hands down my pants to warm them up enough for another attempt. We eventually get all our gear on, now wearing every layer of clothing we have, including two down jackets each. Both of us are protected by not less than six inches of high-tech mountaineering clothing, most if it down feathering, but we still feel the burning of the cold, the biting of the wind. Our water bottles, which were full of boiling water not long ago, are now clogged with ice. We have to keep moving! I don’t think I’ve ever been this cold.

The sun begins to rise as we crest over the undulating glacier, blissfully albeit temporarily alone. Michael takes out his camera and captures a moment of this beauty. For weeks after taking these photographs, his fingertips remain numb from frostnip, the infancy of frostbite.

A magical sunrise lifts our spirits as we climb Island Peak in freezing cold temperatures and relentless wind, wearing every bit of clothing we have.

At around 7 a.m., we reach the summit! We permit ourselves a few short minutes to revel at the superlative views of some of the world’s highest mountains; compared to the giants surrounding us, we are on a molehill at a little more than 20,000 feet. There is nowhere else like this on Earth. We soon head down, thankful to be amongst such grandeur.

Our brief visit to the summit platform of Island Peak with Lohtse looming behind us.

Snow blows in the strong winds, keeping the temperature very low despite sunny skies, as we descend Island Peak.

The final headwall before the summit of Island Peak with a teams slowly making their way up the fixed rope; fortunately, we were the first team to arrive at the summit, which allowed us to avoid this crazy bottleneck.

It’s amazing that we’re here in the Khumbu at all, let alone able to climb, given that Michael was injured in an avalanche not more than two weeks ago. Bummed by his accident in the Rolwaling and our necessary retreat back to Kathmandu, we received very good news when an x-ray revealed that Michael’s heel was not broken. The soft tissue damage, however, was severe. Doctor’s orders: rest and soak it in hot water. He did that for two days. But every day we were in the city the weather was perfect (all 3 of them), and we just couldn’t watch the best of the season go by from our ratty hotel balcony. So we booked a flight to Lukla, the launching point into the famous Everest region, and coincidentally home to “the world’s most dangerous airport,” a short runway cocked at 12 degrees downhill and surrounded by jagged peaks. Our justification in returning to the mountains was that we could hire a porter and take it slow to let Michael’s heel heal along the way. Sound recovery plan, right?

The airport in Lukla (yep, that’s the entire runway) and our itsy bitsy plane.

We met our pre-arranged porter in Lukla: a skinny teenage boy with gelled hair and a bright blue, clean jacket that perfectly matched his bright blue, clean shoes. “So where’s our real porter?” I wanted to ask, but didn’t. Hey, people surprise you, right? Wrong. He was everything I expected and worse. He went half our speed, carrying less weight than we were, probably because he was texting most of the time (I’m not kidding). But it was his attitude that really got to us. He told us that many of our clearly do-able plans were “impossible,” became irritable when we deviated from our initial itinerary or didn’t stay at his relatives’ lodge, and at all other times just sat awkwardly next to us wherever we went.

It did not help that we were trekking at the height of the tourist season through one of the most congested areas in all of the Himalaya. Going from the Rolwaling (Click HERE to read about the Rolwaling), to the Khumbu was like going from running on a lonely mountain trail to the Boston Marathon. A well-aimed snot rocket became a tool for getting personal space. Yaks weren’t fazed by plowing right through you. Lines formed to cross huge suspension bridges as flabby and frightened Everest Base Camp Trekkers crept over, holding on for dear life, except, of course, when they had to take a selfie.

The trail from Lukla to Namche Bazaar, constantly congested with trekkers, porters, and yaks.

Warning: I am about to rant. The Khumbu trekking culture is a dreadful part of an otherwise incredibly beautiful area. As avid climbers, we’ve developed certain notions about mountain etiquette – how a person should act in the mountains. These notions are based in the showing of respect, the ability to be self-reliant, and concerns about both safety and the environment. In our view, the Everest Base Camp experience is perhaps the world’s ugliest version of hiking, from an etiquette standpoint. We found that many (not all!) “Everest Base Camp Trekkers” (EBCTs) are bucket-listers of an unfriendly and rather sorry breed, comprised mostly of middle-aged or early-20-something Europeans and Asians who lack any real hiking experience or ability, and who generally have no business being in the mountains, let alone the Himalaya. Many of those same EBCTs are shockingly self-congratulatory, arriving with pre-made posters of themselves to sign and hang in whatever lodge will put them up; many “teams” wear brightly-colored matching Gortex jackets, followed by brightly-colored matching luggage (carried by yaks and porters, of course) sometimes complete with flags – yes, team flags! – rising out of their packs (their tiny, light day packs). All of this is to flaunt an accomplishment that thousands and thousands of people do every year. Moreover, and unlike what we saw in the Rolwaling, many of the Sherpas here pander to and exploit the ignorance of these tourists, guiding them down clogged trails where it is impossible to get lost. The guides are often of dubious fitness, rigidly attached to a pre-set itinerary, and without any real mountain knowledge or experience themselves. Of course, there are numerous exceptions, but my generalizations are based on well-supported anecdotal evidence. Please forgive me for my cynicism and condescension, but, as a matter of principle (and perhaps a bit of adolescent “take that!”), we absolutely refused to go to Everest Base Camp.

A small sample of the EBCT culture.

I had to check my attitude a couple of times, mainly in those first few days, but then we hit a turning point. After two days on the trail, Michael said it was up to me whether to keep our porter… so I fired him on the spot, divided up our gear, and brought Princess Piggy (that’s my pack) back to her full glory at about 70 pounds. From that point on, we were self-supported. Within five minutes, we rounded a corner and had our first view of Mt. Everest looming over the wide-open, breathtaking valley. It was as spiritual of an experience that one can have on a busy hiking trail. This was a new beginning!

A major turning point: just after we fire our porter and divide up our gear, we turn the corner and have our first view of Everest!

With giant gear-laden packs, our trail cred instantly shot sky high. The porters’ looks of cold indifference were transformed into comments like “Strong man! Strong didi [sister]!” and “Where from? Where going?” We were turning heads, causing chuckles of disbelief, and becoming subjects in the EBCTs’ photo books (A yak train! Click. Mt. Everest! Click. Climbers! Click.). Even with the heavy weight, we were euphoric with autonomy and freedom.

Euphoric celebration of being self-supported in this AMAZING place!

We now had the flexibility to do what we wanted, when we wanted. Our first goal was to get off the main Everest Base Camp trekking route and visit places where we could better appreciate (and photograph!) the dramatic and austere beauty of the Himalaya. Soon, we were at traveling by ourselves on rudimentary trails, with unfettered vistas of the world’s highest mountains. Unfortunately, Michael was beset by illness and injury the entire trip – his avalanche injury refused to heal (shocking!) and he developed both a sinus and respiratory infection that left him coughing up yellow gunk the whole time. Even so, his excitement kept him climbing onward, always thinking of the next viewpoint or sunset with photography gear in tow.

Despite the extreme discomforts and various ailments, we felt wildly successful. Ultimately, we climbed many peaks in the three weeks we spent in the Khumbu, including Island Peak (20,300 ft), Lobuche East Peak (20,100 ft), Pokalde (19,050 ft), Kala Patthar (18,200 ft), Point 5551 (18,200 ft), Chukhung Ri (18,000 ft), Gokyo Ri, twice (17,500 ft), and Awi Peak, and traversed three 18,000+ ft. passes (Kongma La, Cho La, and Renjo La). Our favorite summit was Lobuche East, which we had all to ourselves on a bright sunny day with incredible views of Mt. Everest and the rest of the Himalaya range.

Taylor climbing Lobuche East with the massive Khumbu glacier on the left making its way down towards Ama Dablam in the distance and the face of Cholotse demanding attention on the right.

Basecamp below Lobuche East, with shooting stars performing like a light show.

Our hardest day was climbing Pokalde, going round-trip from Dingboche over Kongma La pass. We left at sunrise and did not return until well after dark with a net elevation gain – and loss – of more than 6,000 feet over many, many miles, all at an altitude higher than the tallest mountain in the continental United States. We took our one and only full rest day after that!

A panoramic view from the summit of Pokalde at 19,050 feet.

Taylor climbing Pokalde with Ama Dablam dominating the background.

The magic of the mountains was most tangible the evening we spent at Kala Patthar, a famous high viewpoint situated across the valley from Mt. Everest, although it is Nuptse’s dynamic and graceful summit reaching for heavens that steals the show.

Watching the sunset over Everest and Nuptse from Kala Patthar.

While the colorful hues of sunset were captivating, the real treat was the full moonrise, which Michael had figured out would occur only 30 minutes or so after sunset. As the other sunset-watchers made their way back down to the settlement 1,400 feet below, we hunkered down in some rocks, alone near the very top of the world, and waited. Soon, beams of light kissed the ridgeline of Everest and slowly morphed into a perfectly circular, glowing orb over its summit. We were the lone witnesses to this incredible event… lone witnesses who were soon scurrying down the trail in the dark, headlamps bouncing, in order to make it back in time for dinner at our teahouse!

We witnessed a magical moment as the full moon rose over Everest.

The trekking infrastructure of the Khumbu is rather glorious and allows for a unique and relatively cushy trekking experience. See our Beta Version for more detailed information. Every few hundred meters along the wide trails are “teahouses,” which are lodges with cheap rooms and hot meals. We fell into a regular routine that went something like this:

7:00am: We crawl out of our warm sleeping bags when the sun hits the window, using the provided blankets as extra padding for the thin, hard mattresses. As the main source of heat at high elevation, the sun is absolutely essential to being even remotely comfortable outside.

8:00am: We sip on milk coffees and eat breakfast, waking up slowing and buying time before we have to pack our bags and hit the still-cold trail and hike to our next destination, anywhere from 2-6 hours away.

We find a new lodge, aiming to stay at whichever is the smallest and least popular, with the moral benefit of supporting a local family and the practical benefit of hearing less bedtime reflections and potty noises from other travelers through the paper-thin plywood walls. Solar power is (wisely) a primary energy source.

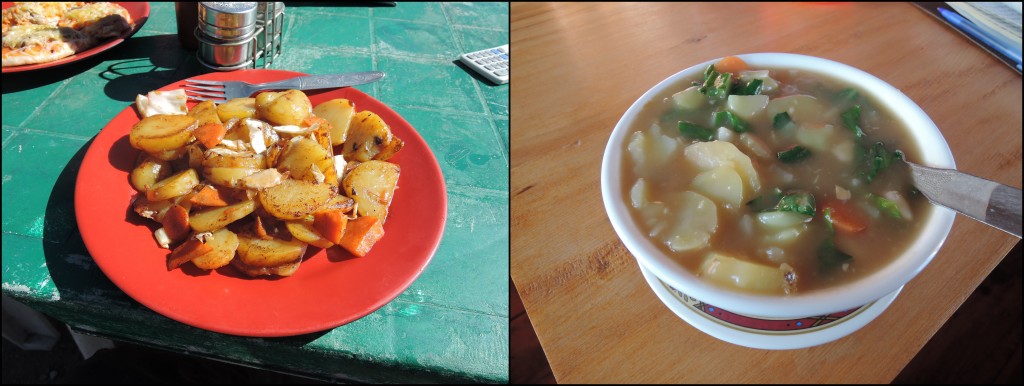

12:00pm: We eat lunch, which is a rotation between fried noodles, fried potatoes or fried rice, topped with a rotation between vegetables, eggs, and tuna. Sometimes we switch it up with Sherpa Stew, a hearty concoction that was different every time.

12:30pm: We take off for an afternoon excursion, usually hiking to a high point above the settlement, where we watch the afternoon clouds roll in and the temperature drop to below freezing. This photo was taken on our way down from Chukhung Ri, an 18,000 ft peak over the settlement of Chukhung.

Some of our afternoon excursions brought us to absolutely incredible viewpoints. This one, Gokyo Ri, was so spectacular that Michael climbed it twice to take more photos.

4:00pm: We sit in the common room of the lodge, shivering as we attempt to pass the time with games, books, and conversation.

Once the sun goes down, a fire is started in the dining room stove, fueled solely by dried yak dung. Like firewood, yak dung is stacked outside the lodges, ready to be used for the trekking season.

6:00pm: We inhale our dinner, usually dal bhat, the traditional Nepalese meal of rice with curried potatoes and vegetables and a lentil-based broth that may or may not include rocks (so chew carefully!). We are in bed around 7:30pm when we can’t take the cold any longer.

Our hands took a beating, aging decades in mere days from the constant exposure to sun, wind and a very dry climate.

We were totally exhausted by the end of our trip. Thankfully, we met Brandon, Carolyn and Bridget, like-minded trekkers from the United States finishing up their trip. We trekked in tandem for the next several days, Michael and Brandon geeking out about photo and climbing gear, and Carolyn, Bridget and I soul-searching about upcoming life changes. It was a welcome change of pace that made the final trek back to Lukla much more enjoyable.

We strike poses with our trekking companions, Brandon and Carolyn, as we wait for sunset up on Gokyo Ri.

Prayer flags surround us as we climb up and over our final pass, Renjo La, and start our long descent out of the Khumbu.

It was with mixed memories of high highs and low lows, literally and metaphorically, that we flew back to Kathmandu. This was an EXPERIENCE that we will never forget… but life is hard in the high Himalaya and we’ve been dreaming of warm beaches in Thailand. We are ready for the next chapter of our adventure!