I sit on a balcony at our hostel overlooking an overgrown garden, the bushes and vines suffocating old plastic tables and chairs. On the other side of this small jungle, seven men butcher a hog on a large sheet of tin; the same tin used for fences, gates and roofs all around Kathmandu. It’s hard to peel my eyes away from the stump used as a butcher’s block and the piles of organs, meat and bones being sorted, dogs hovering nearby hoping for scraps. We have left the United States; every one of my senses tells me so.

Birds flying around Swayambhunath Temple (“The Monkey Temple”) in Kathmandu, Nepal

A girl sells candles at the base of Swayambhunath Temple

One of many, many photos Michael took of the monkeys that dominate Swayambhunath Temple

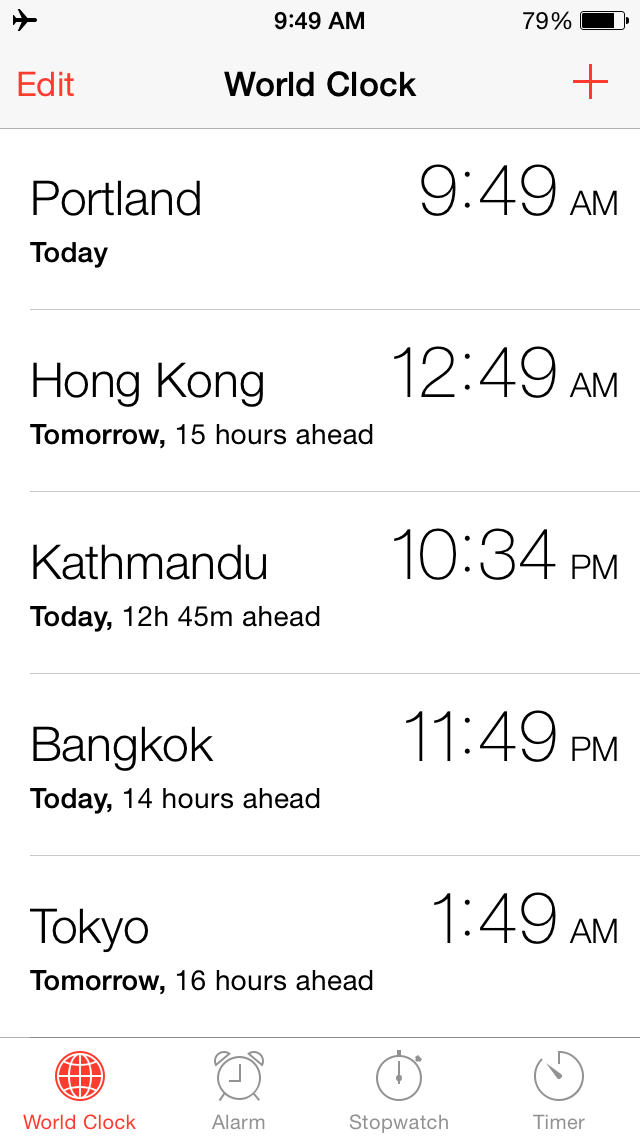

On October 1, 2014, we began our journey to the other side of the world. It took 23 hours of travel time, chasing the dark night around the globe, with a brief stopover in Hong Kong and a time warp where we lost almost an entire day jumping through time zones. Inconveniently, Nepal is 12 hours and 45 minutes ahead of Pacific Standard Time. Thankfully, the Nepalese like their sugar with milk and coffee (as do I).

The “World Clock” on my phone as I attempt to figure out what time it is.

Kathmandu is a climber’s Disneyland. In the Thamel district (the “tourist ghetto”), every other shop or hotel doubles as a travel agency, ready with proposed itineraries for how to experience Nepal. Map shops set Michael’s eyes aglow, but the scarf shops had my heart. We spent the first several days dodging traffic in the streets, seeing the city sights, and developing our plan for climbing and trekking in the Himalaya.

Michael, overwhelmed with joy at the map store of his dreams. It was hard to pull him away…

It was ambitious. With up to 90 days in Nepal and the mountains our priority, we planned to first trek through the remote Rolwaling Valley, one of the steepest and shortest ways to access the Himalaya. From there, we could cross a 19,000-ft pass into the Khumbu region, where Everest resides as the illustrious VIP. We anticipated the first two days to be the crux, with about 9,000 feet of hiking with fully-loaded packs and the assistance of one porter, Jengdu (the guide we thought we needed as per government regulations, Nima, was collecting our permits and meeting us in a few days, but had acknowledged that we did not want nor need him to join us on our climbs).

One of many signs along our trek up the Rolwaling Valley (with inconsistent spelling of almost everything)

After a long day on a local bus, we began our ascent. As we put our packs on, Michael spied a meat hook and couldn’t resist. Each pack came in at 25 kilos, or about 55 pounds. I wished I hadn’t known that before starting off. Jengdu (along with every other porter) carried his load by a strap around his forehead. I named my pack Princess Piggy. At 85-litres, she’s a hefty one and we paid a dowry for her. I imagined her with a voice like Miss Piggy from The Muppets, commanding me forward as her personal chariot, the clanking of my necklace on my chest strap like a dainty whip urging me forward.

Our porter, Jengdu, carrying his load with a head strap under his baseball cap.

The trail wasn’t like a staircase; it was a staircase. The porters ahead and behind me called responsive cheers and yips back and forth, keeping up our energy. We felt strong, everything was new and intriguing, and we could stop for coffee, tea or a snack at our leisure, with each well-spaced community providing some kind of lodge (commonly called a teahouse) ready to serve weary trekkers.

The trail up, up, up through the Rolwaling Valley

Houses in Beding, one of the communities we stayed in along the way

Over the next three days, we watched the dramatic change in climate from overgrown jungle, complete with leaches and the deafening buzz of insects, to a mountain forest that reminded us of the Pacific Northwest, to the high alpine where only pokey bushes and rocks can thrive. Giant, cascading waterfalls were around every corner, often with an exposed and dubious suspension bridge crossing the raging rivers. It was breathtaking.

Looking down on Na, the mountain village where we stayed for most of our time in the Rolwaling

Crossing one of many large suspension bridges on the trek up the Rolwaling

Literally. I had no breath left in me by the time we reached Na, the summer settlement at ~14,000-ft that would be our home base for acclimatization. Somehow I managed to attract the worst head cold I could remember, which worked in tandem with the altitude to defeat my strength. With no insulation in any of the buildings and a fireplace that put out vastly more smoke than heat in our teahouse, my condition grew worse.

The inside of our teahouse with the morning light streaming in

Despite my sickness, Na was amazing. Michael, Nima (our guide who joined us) and Jengdu were able to set out on several acclimatizing excursions and I spent most of my time chatting with fascinating foreigners. Two distinct types of foreigners roamed the village: the trekkers, mostly in their 50’s or older, were parental and inspirational; the climbers, about our age and mostly professional guides, were hilarious and great company. Without the distraction of smartphones and with almost nothing else to do, we enjoyed lots of story swapping over nak milk tea (yaks are male, naks are female, and both were abundant) and chang (the local rice-based alcohol) with both groups of people. I found a new normal in witnessing the daily life of our teahouse host, Ani (that’s Sherpa for auntie), from milking a nak for our morning coffee, to churning the milk into butter, to drying yak dung for the fire and herbs for the tea, and cooking meals over a large wood-burning stove. Despite being constantly cold and not seeming to feel any better, I was getting into the swing of a simple and fascinating life.

Ani milking a nak for our morning coffee

One day, we hiked to the Buddhist monastery on the hill overlooking Na. We shared tea and “po-ta-toes” (each vowel in the word enunciated with staccato) with the monk caretaker and learned some of the holy history of this incredible place, including how the second Buddha tamed the local deities (five sister goddesses that reside in their personal mountain-temples) as he meditated in the cave inside of which the monastery was built. In that very cave, the caretaker performed a 30-minute Puja, or a blessing ceremony, for our safety, complete with incense, chanting from sacred text, and the beating of ancient drums, all done by candlelight. During this moving ceremony, we saw the blue skies turn grey and then white with heavily blowing snow through the single, tiny window. A big storm had rolled in and it snowed all night long. This was the same storm that hit the Annapurna region, tragically resulting in so many injuries and deaths; we would not know of this tragedy in our isolated village for several days.

Taylor with the Buddhist Monk, the caretaker of the monastery above Na

Michael and Taylor in front of our teahouse watching it snow… and snow and snow and snow.

Na after the snow storm

A yak wanders through town, clearly used to this weather

The sun came out the next day and Michael and several others headed up to the basecamp of Ramdung to see if it was climbable. I was left in Na to sniffle and sneeze and cough my way slowly to some kind of workable health. Despite the sub-freezing temperatures, Michael was able to capture some of the nighttime grandeur of the Himalaya.

Sunset at Ramdung base camp with Marcol and Phillip

A cold and starry night in the Himalaya

There was far too much snow to climb Ramdung. But with the company of Nima and two Swiss climbers we had befriended in Na, Marcol and Philipp, Michael began trudging towards Yulang Ri, not necessarily expecting to summit, but taking the opportunity to play in the mountains on a perfect, sunny day. All was going well until they got to the toe of the glacier, which would lead them up the climbing route. After an assessment of the avalanche possibility, they decided the risk, even in a worst-case-scenario, was relatively low and they would proceed with caution.

It was all well and good until about 100 feet up, almost to the crest of the slope, when Michael (who was leading) took a single step and the character of the snow changed abruptly. He tried to quickly traverse out, but it was too late and the crown broke. The top 3 feet of snow was severed from the sheet of ice below it and slid down, carrying Michael and Marcol with it. Michael landed on a boulder at the bottom and was buried to his chest – losing his sunglasses in the process. Marcol was awkwardly buried up to his neck, but was otherwise unharmed. After checking in with each other and digging through the snow to recover lost items, they turned back. Without sunglasses, Michael knew he had a very limited time before he became affected with snow-blindness and hurried back to base camp.

Marcol, Philipp, and Michael, temporarily euphoric at surviving the avalanche

As the adrenaline subsided, Michael soon realized that he could hardly walk on his right foot. He hobbled his way down to base camp (and then to Na), his plastic boot doubling as a pseudo-cast. There’s no doubt that his foot would have been much more injured in the avalanche had he not been wearing plastic boots.

Not knowing whether his foot was fractured or only badly bruised, we gave ourselves two days in Na to figure out our plans. As we waited, we started to hear tidbits of information that sounded unreal. “30 people dead in accident in Annapurna. Hundreds hurt. Hundreds still missing.” Something had to be getting lost in translation, but there was no way to confirm any information without telephone or internet connectivity. On the second day of our wait, the snow started again, which was the nail in the coffin. Michael’s foot had hardly improved and I was about done with shivering through every second of every hour in Na. So down we went, sniffling and hobbling and in generally poor condition; however, we were blessed with the generous assistance of an American couple who, trekking with the luxury of a full support crew, allowed us to add some of our weight to one of their porters and join them on their chartered bus back to Kathmandu.

Michael using his trekking poles as crutches and his plastic boot as a cast as he descended down 8,000 feet with a hurt right foot

Porters traveling down the Rolwaling Valley, all carrying their loads with a head strap

Taylor hiking in the Rolwaling Valley, alive with the colors of fall

After three days of descending 20+ miles, a total of 13,000 feet (for Michael), and a full-day bumpy bus ride, we made it back to the bustling, noisy, and barely-functional chaos that is Kathmandu. We reassured our parents of our safety, learned more of the disastrous Annapurna avalanches, and obtained X-rays of Michael’s foot at a medical clinic; fortunately, the X-rays showed no major fractures, but, as Michael says, his heel “hasn’t gotten the memo” and continues to be very painful. According to the doctor, Michael’s foot has substantial soft-tissue damage – ligaments and tendons and stuff – but should eventually heal with rest. We both feel incredibly lucky with the diagnosis.

So now we will wait and heal for a little bit, soak in the endearing calamity of the Kathmandu valley, and scheme our next adventure in the Nepal Himalaya.